Demystifying Form 4797: How Asset Dispositions Impact Business Valuation

Welcome back to the podcast blog! In our latest episode, we dove deep into a crucial, yet often overlooked, aspect of business valuation and transaction structuring: the impact of asset dispositions. It’s easy to get caught up in revenue multiples and profit margins, but the way a business handles the sale or disposal of its assets can significantly distort its reported earnings, leading to mispricing and unnecessary friction during a sale. In this post, we’re going to unpack IRS Form 4797 and explore how these dispositions can be normalized to reveal the true, sustainable performance of a business. If you missed the episode, you can catch up on all the details here: ONWC Chain From Asset Dispositions to True Up.

Understanding Form 4797: What It Is and Why It Matters

At its core, IRS Form 4797 is designed to report the sale or exchange of business property. This isn't about selling your inventory to customers; this is about the disposal of capital assets – for example: machinery, equipment, vehicles, buildings, and other long-term assets that a business uses to operate. When a business sells any of these types of assets, the tax implications are reported on this form. Why is this so important for business valuation? Because the gains or losses generated from these sales are not always treated as simple capital gains or losses. This is where the concept of 'recapture' comes into play, and it's a major driver of earnings distortion.

Imagine a company that sells a piece of equipment for more than its depreciated book value. It might seem like a straightforward gain. However, the IRS often 'recaptures' a portion of that gain as ordinary income, up to the amount of depreciation previously taken on the asset. This means that what appears as a capital gain on the surface can, in part, be taxed as ordinary income. Conversely, if an asset is sold for less than its depreciated value, it results in a loss, which can also impact reported earnings. These fluctuations, especially if they are one-time events, can paint a misleading picture of the business’s ongoing profitability. If a buyer, or even a seller, applies valuation multiples to earnings that have been artificially inflated or deflated by these asset disposition events, the business will inevitably be mispriced.

In other words, the sale or exchange of business property can introduce “noise” into earnings that needs to be quieted.

The 'Recapture' Concept: How Asset Sales Can Distort Earnings

The 'recapture' rules are the primary mechanism by which asset sales distort earnings. For certain types of depreciable property, like Section 1245 property (personal property and certain other tangible property), any gain recognized on its sale is treated as ordinary income to the extent of the depreciation previously claimed. If the gain exceeds the total depreciation taken, the excess may be treated as a capital gain. For Section 1250 property (real property), the recapture rules are a bit more nuanced, generally applying to the extent that accelerated depreciation was used. The key takeaway here is that the tax treatment of an asset disposition is not always a simple addition or subtraction to the bottom line as one might initially assume. It's a complex interplay between the original cost, accumulated depreciation, and the sale price.

Consider a business that has been aggressively taking accelerated depreciation on its machinery to reduce its tax liability. When it's time to sell that machinery, even if it sells for more than its original cost, a significant portion of the gain will be treated as ordinary income due to the depreciation 'recapture'. This can significantly inflate the 'reported' earnings for that year, making the business appear more profitable than it actually is on an ongoing basis. Conversely, a sudden write-off or sale of obsolete equipment at a loss can depress earnings in a particular period, making a healthy business appear less valuable. These events are what we refer to as 'noise' in the financial statements. Applying valuation multiples to this 'noise' is a recipe for disaster. We need to normalize these events to understand the true, sustainable operating performance.

Distinguishing One-Time Events from Structural Asset Cycles

A critical step in demystifying these dispositions is to differentiate between a one-time event and a recurring, structural part of the business's operating model. A one-time sale of surplus equipment that the business no longer needs is an event that will not repeat. However, in certain industries, the sale of assets is an intrinsic part of the business cycle. Think about fleet-based businesses, such as rental car companies or logistics firms with large truck fleets. These businesses operate on a planned asset turnover cycle. Vehicles are purchased, used for a defined period (e.g., two years), and then sold as part of a routine replacement schedule. In these cases, the gain or loss on the sale of these vehicles is not a random event; it’s an anticipated and recurring component of their business model.

For these structural asset cycles, a 'steady state' view is essential. This involves analyzing the historical patterns of asset turnover, typical proceeds from asset sales, the cadence of asset replacement, and the recurring earnings impact of these cycles. Instead of looking at a single year's financials where an asset sale might have artificially boosted or depressed earnings, we need to look at a trailing twelve-month period or even longer, accounting for seasonal fluctuations, to model the asset cycle as a normal operating pattern. This approach normalizes the financial picture, presenting buyers with a clear understanding of what to expect in terms of ongoing asset management costs and potential disposition proceeds. This eliminates buyer skepticism because we're not hand-waving; we're presenting a defensible, modeled expectation based on historical operational reality.

Fleet Businesses: A Case Study in Normalizing Asset Turnover

Let's take the example of a car rental company. Their primary assets are vehicles. They buy fleets, rent them out, and then sell them after a certain mileage or age. This selling of vehicles is not an anomaly; it's fundamental to their business. If the company sells a batch of vehicles in a given year for a significant gain due to favorable market conditions, that gain distorts their net income for that year. However, a buyer needs to understand the ongoing economics of the business, which includes the regular cycle of selling older cars and buying newer ones. To normalize this, we would look at the average profit or loss realized from vehicle sales over several years, the typical depreciation schedule, and the cost of acquiring replacement vehicles. We would then adjust the reported earnings to reflect this normalized asset turnover. This means treating the disposition proceeds and associated costs as a predictable, recurring element of the business, rather than a one-off event. This allows for a more accurate valuation, as the multiple will be applied to the true, maintainable earnings of the rental operation, not earnings artificially boosted by an asset sale.

Section 179 and Depreciation: Timing Is Everything

Beyond the sale of assets, the timing of depreciation deductions, particularly through mechanisms like Section 179 of the Internal Revenue Code, can also significantly distort earnings. Section 179 allows businesses to expense the cost of qualifying depreciable property in the year it is placed in service, rather than depreciating it over several years. This offers substantial tax benefits, allowing businesses to reduce their taxable income immediately. However, from a valuation perspective, this 'rapid depreciation' can make a business's P&L look worse in the current year, even if the business is healthy and investing in its future. Conversely, in future years, the absence of these depreciation deductions can make earnings appear artificially better because the deductions were pulled forward.

The solution, again, lies in adopting a 'steady state' thinking. We need to normalize these fluctuations. The question becomes: what level of capital expenditures (CapEx) and depreciation is *required* to keep the business operating in its current state? This allows us to separate the cash reality of asset replacements from the tax timing of deductions. When buyers point to earnings being depressed due to high depreciation expenses, we can normalize by focusing on maintenance CapEx levels and a steady-state depreciation rate that reflects the ongoing needs of the business, not the tax strategies of a particular year. This way, multiples are applied to maintainable performance, not to earnings that are artificially influenced by tax timing elections. It's crucial to understand the difference between tax accounting and economic reality when valuing a business.

Normalizing for 'Steady State': Finding Maintainable Performance

The concept of 'steady state' is the bedrock of normalizing earnings. It’s about stripping away the noise – the one-time events, the tax strategies, the temporary market fluctuations – to reveal the core, repeatable profitability of the business. This involves asking probing questions: What are the true ongoing costs of maintaining the business's operational capacity? What are the predictable revenues and expenses? For asset-heavy businesses, this means understanding the replacement cycle of key assets and the associated costs and revenues. It requires a forward-looking perspective, projecting what the business will look like under a new owner, assuming the same operational model. By normalizing for these factors, we ensure that the valuation is based on the business’s enduring earning power, not on a snapshot of financials that may be distorted by non-recurring items. This creates a more robust and defensible valuation, reducing the likelihood of disputes and ensuring a fairer transaction price.

Operating Net Working Capital: Beyond the GAAP Definition

When we talk about working capital in the context of business transactions, we often start with the standard accounting definition: Current Assets minus Current Liabilities. While technically correct, this GAAP definition is often insufficient for deal purposes. In M&A, we need to isolate the *operating* net working capital – the capital that is directly tied to the day-to-day operations of the business and is essential for it to function. This means excluding non-operating items such as excess cash, interest-bearing debt (which is financing, not operational), and owner or related-party transactions that don't reflect the business's normal operations. The core formula becomes: Operating Net Working Capital = Operating Current Assets - Operating Current Liabilities. The addition of the word 'operating' is crucial; it signals a shift from a purely accounting perspective to a transaction-focused operational perspective.

The Process-First Method for Working Capital Disputes

One of the biggest sources of friction in M&A deals is disputes over working capital adjustments. The most effective way to mitigate this is to adopt a 'process-first' method. Before anyone even discusses specific numbers or a target working capital peg, all parties must agree on the definitions of what constitutes operating working capital. What items are included? What items are excluded? Once these definitions are crystal clear and documented, the next step is to agree on the method for calculating the target peg. A common and effective method is to use the average of the month-end operating net working capital over a trailing 12-month period, calculated using the exact same inclusion/exclusion rules agreed upon earlier. For seasonal businesses, this average should be adjusted for seasonality. The final purchase price adjustment is then a dollar-for-dollar true-up: Closing Operating Net Working Capital minus Target Operating Net Working Capital. This process-first approach, emphasizing definitions and methodology before numbers, dramatically reduces ambiguity and adversarial negotiations. It ensures everyone is working under the same set of agreed-upon rules, leading to a smoother and more predictable closing process.

Alignment is Key: Connecting Working Capital to Asset Allocation Reporting

The consistency of our approach cannot stop at working capital. It must extend to how the entire transaction is reported, particularly for tax purposes. In applicable asset acquisitions, the IRS Form 8594, Asset Acquisition Statement, requires parties to allocate the purchase price among the acquired assets. The instructions for this form describe a 'residual method' of allocation. The critical takeaway for deal advisors is not to become tax preparers, but to ensure that the operating net working capital definitions agreed upon during the deal negotiations align with how the transaction is described, allocated, and reported on forms like 8594 and its state-level counterparts. Mismatched reporting between the purchase agreement and tax filings can trigger audit flags and lead to significant issues down the line. If there's a working capital true-up after closing, that adjustment affects the final purchase price consideration and should be reflected consistently in all subsequent reporting. By maintaining this alignment, we build a more robust and defensible transaction structure that stands up to scrutiny.

Form 8594 and State Forms: Ensuring Consistent Reporting

It's not just about federal tax forms; state tax forms often mirror the reporting requirements of Form 8594. For example, some states have their own versions of asset allocation reporting. The goal is to ensure that the story told to the IRS is the same story told to state tax authorities, and, more importantly, that it aligns with the economics of the deal as agreed upon in the purchase agreement. If working capital is adjusted post-closing, this has a direct impact on the final purchase price. This adjustment should be consistently reflected across all reporting. A practical approach is to provide a sample Form 8594 to buyers and sellers, based on the final post-closing true-up, advising them to take this model to their tax preparer for accurate filing. This proactive measure helps prevent discrepancies and audits by ensuring consistency across all parties and all reporting channels. The consistent process, pegged to the final true-up, reduces the likelihood that the deal's economics and its reported story diverge.

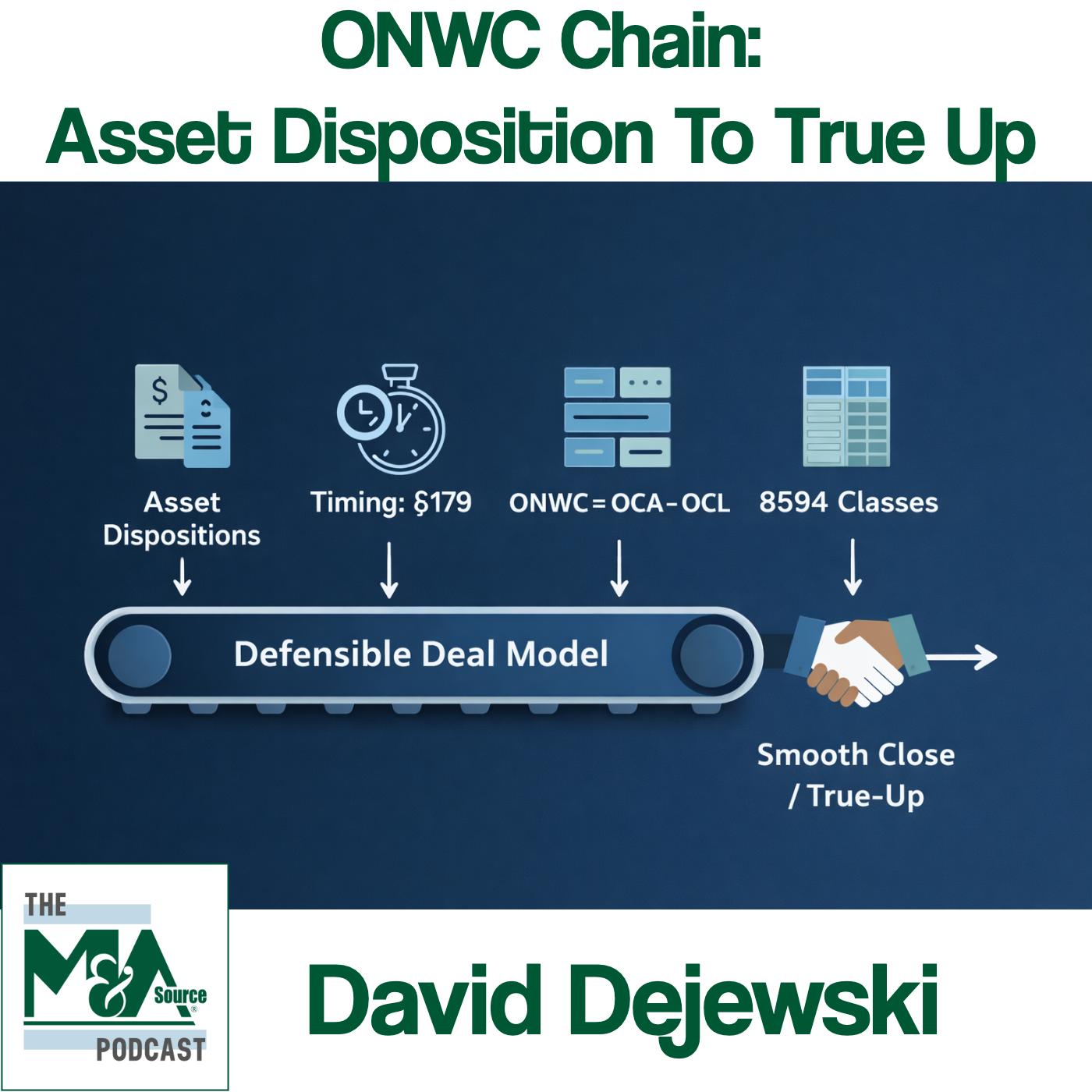

The Unified Framework: A Summary of the Four-Link Chain

To tie it all together, we've discussed a unified framework composed of four interconnected links. First, we must normalize earnings to ensure that valuation multiples are applied to maintainable performance, eliminating one-time gains or losses and the distortions caused by tax timing effects. Second, we need to classify asset dispositions properly, distinguishing between one-time events and structural asset cycles. Third, we interpret Section 179 and other depreciation choices as timing issues and normalize to a steady state understanding of the business's needs. Fourth, we define operating net working capital rigorously, agreeing on inclusions and exclusions, and then set the target peg using an agreed-upon historical method for a dollar-for-dollar true-up at closing. Finally, the story told by the working capital definitions must align with proper asset allocation reporting to the IRS and state tax authorities. This integrated approach reduces friction, builds credibility with sophisticated buyers, and makes transactions easier for attorneys and CPAs to document, ensuring a cleaner and more efficient deal process.

Conclusion: Building a Defensible and Frictionless Transaction Process

In our latest episode, “ONWC Chain From Asset Dispositions to True Up,” we explored how seemingly technical IRS forms and accounting principles like Form 4797 and operating net working capital can profoundly impact business valuation. We've seen how asset dispositions, depreciation timing, and the definition of working capital can distort earnings if not properly understood and normalized. This blog post has broken down these complex topics, emphasizing the importance of distinguishing one-time events from structural business cycles, normalizing for steady-state performance, and adopting a process-first methodology for working capital. By applying the unified framework discussed – connecting asset dispositions, depreciation, working capital, and asset allocation reporting – businesses and their advisors can build a defensible valuation, reduce friction during transactions, and ensure a smoother closing process. This approach ensures that the numbers used for valuation accurately reflect the ongoing, sustainable performance of the business, leading to fairer pricing and greater certainty for all parties involved. As always, we encourage you to listen to the full episode to gain an even deeper understanding of these critical concepts and how they can be applied in practice.

Disclosure

The information presented in this article and associated podcast episode is for educational and informational purposes only and is intended to provide general insights into business valuation, transaction structuring, and related accounting concepts. It does not constitute legal advice, tax advice, accounting advice, or investment advice.

The discussion of IRS forms, tax provisions, valuation methodologies, and transaction mechanics is illustrative in nature and may not apply to any specific business, transaction, or jurisdiction. Tax laws, regulations, and interpretations are complex and subject to change, and their application depends on individual facts and circumstances.

Readers and listeners should consult with their own qualified legal counsel, tax advisors, and accounting professionals before making any decisions or taking any actions related to business valuation, tax reporting, or transaction structuring.